When most people decide to start a brand-new church, they do so on theological differences.

Martin Luther, for instance, found that the Catholic emphasis on the union of act and faith, and its practice of granting indulgences for certain religious activities, was inconsistent with his interpretation of Scripture. John Calvin found himself fascinated by the idea of predestination, and Ulrich Zwingli came up with a whole laundry list of things he didn’t like about the Catholic Church.

These were men who founded systems of belief on their own pet theological musings.

Regardless of whether you find their ideas persuasive, you have to at least admit that there is something admirable in pursuing an idea to its natural conclusion, even if that conclusion means revolution.

But the Church of England doesn’t fall into that category.

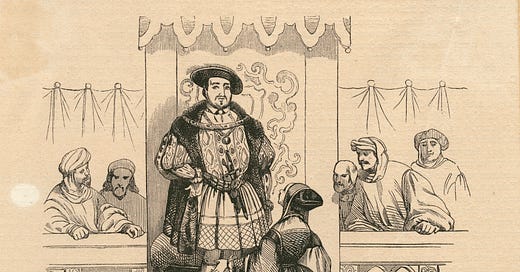

Henry VIII was just 17 when he received a dispensation from Rome to marry his dead brother’s wife, Catherine of Aragon. He had just ascended to the English throne and was setting out to defend the honor of the pope against religious revolutionaries rising in Germany. By all accounts, he was also madly in love with Catherine.

If there was one thing Henry VIII was infatuated with, it was the idea that his son would ascend to the English throne and carry on the Tudor name. Unfortunately, none of the three boys Catherine conceived survived longer than two months and by the time she was 45 and it was clear that no more children would be forthcoming, Henry was obsessed with one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn.

There was just one problem. Henry had received a dispensation to marry Catherine all those years ago, and despite all his best efforts, he could not convince the pope to annul the marriage. So, at the behest of Thomas Cromwell, he did the most obvious thing in the 16th century: he made his own church and had that church annul the marriage.

Henry, of course, didn’t have a pet theological musing. He just wanted to marry another woman so he could have a son, which made him more a schismatic than a heretic. On the other hand, the Boleyns’ family chaplain, Thomas Cranmer (who was appointed the new Archbishop of Canterbury) did have pet theological ideas at odds with Catholic theology. He had spent some time in Germany developing a heretical view of the Eucharist while on a diplomatic mission for the British court, and spent his time as archbishop concocting a liturgy that coincided with that opinion.

As tends to happen when infidelity is involved, Henry VIII didn’t stop with Anne Boleyn. When she failed to produce a male heir, he had her accused of treason and adultery (she was probably not guilty) and beheaded on May 19, 1536.

Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I, would eventually rise to the throne, leaving England in something of a bind. Because the Catholic Church had never actually annulled the marriage between Catherine and Henry, Elizabeth couldn’t both heal the rift between England and Rome and claim to be a legitimate heir (although it’s unlikely she ever wanted to). Nor could she really leave Catholics in England alone, since they had very good grounds for denying her rule — especially while her half sister and Catherine’s surviving daughter, Mary, was alive.

The result was a war on the remnants of Catholicism in England, the importing of puritanical Calvinists, and the English Civil War.1

How’s that for a shameless self-reference? Here’s the link, in case you missed my piece a few weeks ago on the beginnings of the English Civil War:

When King and Parliament Didn't Agree

When it comes to British history, we live in a rather exceptional time.