There are very few political revolutions quite as successful and quite as futile as the French Revolution.

On the one hand, it successfully overturned the French monarchy of the late 18th century; it ushered in an age of rebellion and revolution against the established world order in favor of democracy; and it applied the principles of the Enlightenment (e.g. a spirit of radical individualism and skepticism, so long as the individual did not oppose or question the revolutionary project) to the whole of France.

For a moment, the project looked successful. The blood in the streets dried, the crowds went home, and the counterrevolutionaries sank to their deaths on barges in rivers in Nantes and the Vendée.1 Yet, when all was said and done, the revolutionaries had made a fatal mistake. While dealing with all the internal strife that naturally arises when running a revolution in a country as diverse as France was in the late 18th century, they also managed to pit France against its neighbors on the battlefield with the purported goal of spreading the revolution.

Democracies work well in times of peace when there’s plenty of time to debate issues among elected officials or to hold elections on important national questions. Democracies — and even Republics — don’t tend to work as well when decisions about the movements of troops or the allocation of resources in war must be made quickly. The Roman Republic had solved that issue by appointing a consul in times of war, and the government established by the French Revolution decided to do the same.

What the Roman Republic quickly discovered about consuls is that they tend to get power-hungry. If you’re lucky, you end up with men like Cincinnatus, who simply want to go back to their farms and leave power behind. Those kinds of men are rare, and Napoleon Bonaparte was not one of them.

That Bonaparte was the man France needed to prevent annihilation at the hands of the enemies it had provoked was clear by 1796, when he managed to run a successful military campaign in Italy with a ragtag bunch of troops without uniforms or solid supply lines. He conquered large swaths of the country reaching down into Rome, and took Pope Pius VI captive, put him in a carriage, and transported him up to France to pressure him to give up temporal power over the Papal States. Pius VI died before giving in.

By 1802, Bonaparte had run a coup d’état and had himself proclaimed consul for life (a predictable course of events the government could have foreseen had it studied Roman history a bit more closely). In 1804, he wanted to be emperor.

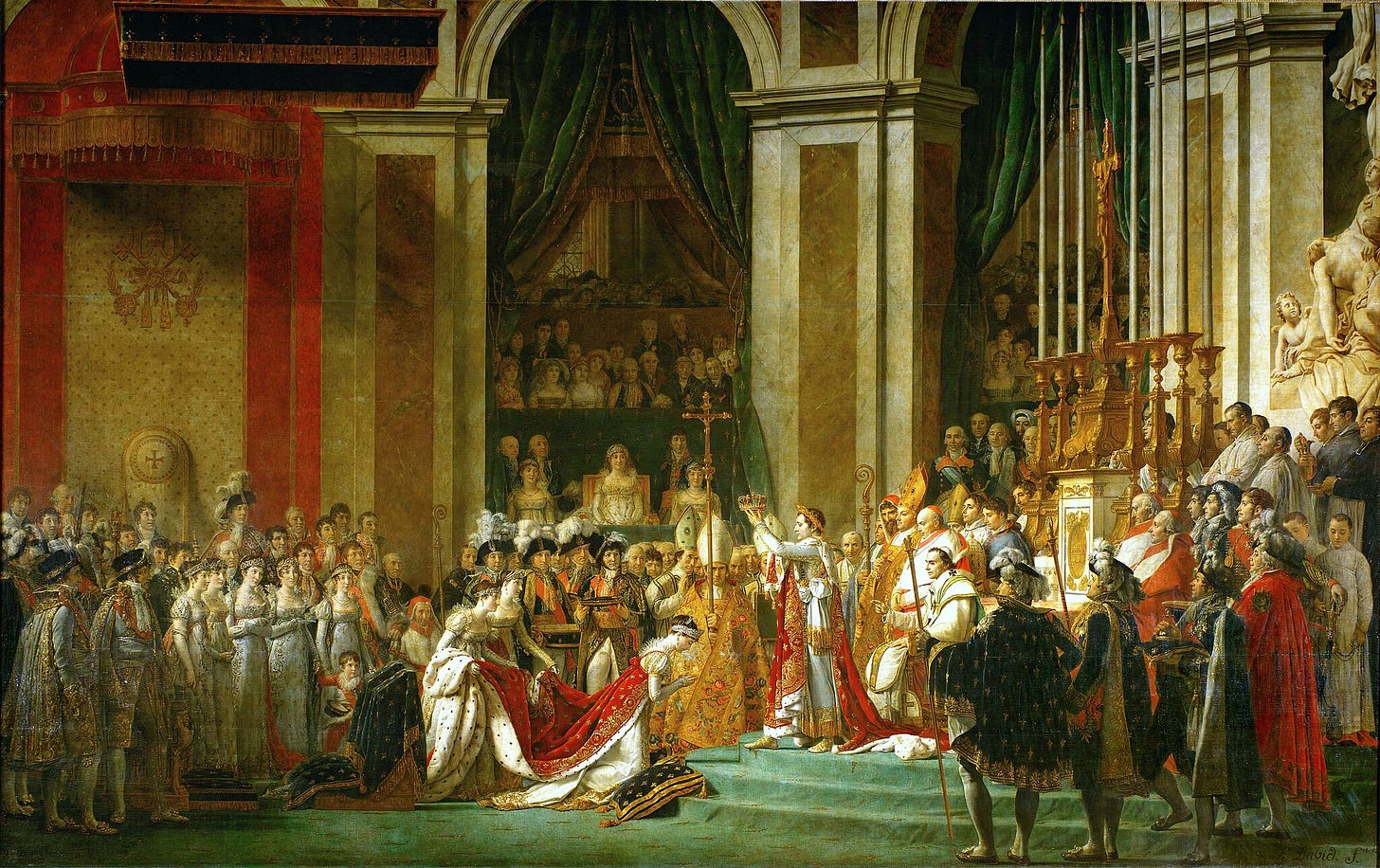

But he didn’t just want to be emperor. He wanted to be an emperor in the style of Charlemagne. That meant he had to persuade the pope to come to Notre Dame (Pius VII was an easygoing man and was eager to ensure the safety of his flock in France), and find a replacement crown for the ancient one destroyed in the Revolution. Both things being accomplished, Bonaparte planned a coronation for Dec. 2, 1804.

When it actually happened, Bonaparte broke with tradition. Rather than letting the pope crown him, he took the crown and placed it on his own head. In the painting Bonaparte commissioned of the event, Pius VII has his hand raised in blessing, but if you look closer at the canvas, it’s clear the painter initially had Pius VII’s hands in his lap — a change that seems intended to serve as propaganda rather than a reflection of reality. The Church, after all, was supposed to be at the service of the State according to the principles of the Revolution; even while the French partook in a ceremony that likely made the architects of the Revolution turn in their graves.

If revolutions feed on blood, they tend to die at pompous ceremonies in ancient cathedrals.

When we think of the French Revolution, we typically think of Paris and we tend to forget that the whole country wasn’t necessarily on board with the idea of regicide. The average Frenchman wasn’t usually murderously opposed to the king, and he certainly didn’t enjoy being conscripted into an army being formed for the purpose of spreading a revolution he didn’t like to distant lands he didn’t care about. More than that, he didn’t like that the French Revolutionary government was bent on killing his priests and burning the churches his grandfathers built. The result was that rural France — especially in the region known as the Vendée — rebelled. The architects of the Revolution, already mad on blood, knew that a counterrevolution doesn’t look good when you’re advertising democracy, so they reacted by running what some historians consider to be the first genocide in modern history. Some areas of France (including the Vendée) lost as much as 20 percent of its population to the Revolutionary government’s “infernal columns.”