In our day of automated spell-checkers, we don’t think much about the fact that there is a correct way to spell “music” or “plow” or that words like “hickory” and “skunk” have made it into our dictionaries.

But in the early 19th century, that wasn’t the case at all. Spelling wasn’t standardized, and dictionaries written by Englishmen didn’t include American species of animals and plants. Dictionaries, of course, were a relatively new thing. Samuel Johnson had published the very first one in 1755, and the Americans had been too preoccupied with fighting a revolution and establishing a new country to publish their own edition any sooner.

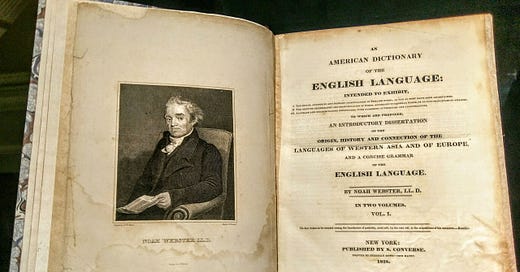

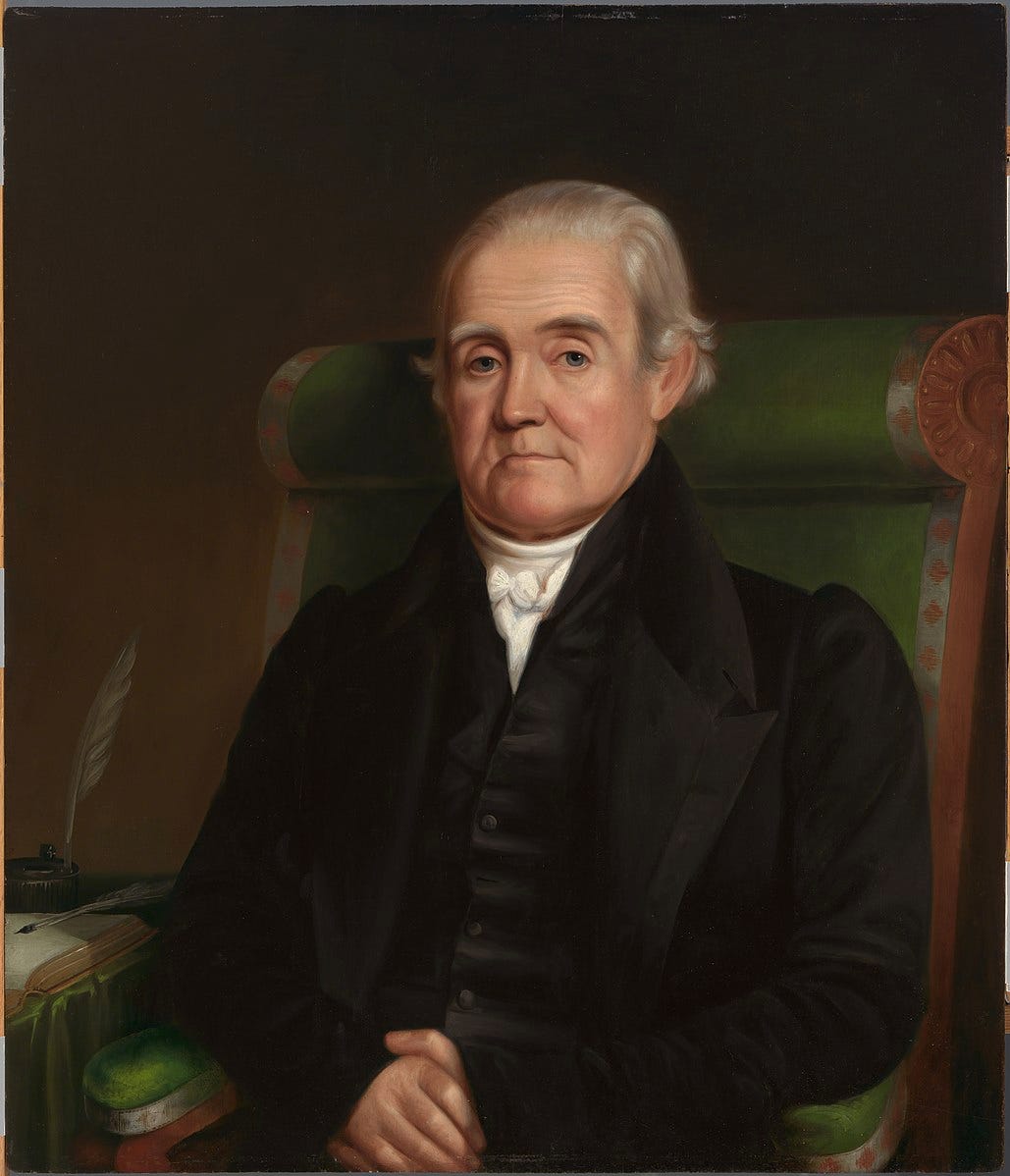

But Noah Webster was determined to change that. As early as 1806, the Yale-educated lawyer published a tiny little book with a very long title: A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language: In which Five Thousand words are added to the number found in the Best English Compends; the Orthography, in some instances, corrected; the Pronunciation marked by an Accent or other suitable Direction; and the Definitions of many Words amended and improved.

In case you didn’t feel like reading that whole title, Webster had messed with things like pronunciation and orthography (the way words are spelled) and apparently thought that the Johnson’s definitions for words were inadequate — and that was just the beginning.

Webster’s Compendious Dictionary was a preview to a project he spent the next 18 years working on: A full-fledged dictionary that outpaced anything anyone in England had done. To get to the final count of 70,000 entries complete with etymology, new spellings, and nearly 10,000 “Americanizations,” Webster learned some 26 languages and developed plenty of opinions on the way words should be spelled.

For instance, he determined that “plow” was a more accurate spelling than “plough” and that “musick” should probably just be “music.” But he lost the battle over tongue, which he wanted to spell “tung,” and women, which he thought should be spelled “wimmen.”

The very first edition of An American Dictionary of the English Language was finally published on April 14, 1828, and it was a bit of a dud. The two-volume set was initially sold for $20 (or $673.26 today) and wasn’t incredibly popular. It became only slightly more so when Webster decided to lower the price to $15 (or $504.95 today).

And yet, despite the fact that it was relatively unpopular initially, Webster’s dictionary and spelling stuck (perhaps because he also wrote a grammar for American students that was used almost exclusively in American schools for the better part of a century).

Even in our age of global communication and gradual standardization, Americans have maintained their own spellings for works like “center” and “color,” and we have Webster to thank.