Defeating Death

Aug. 25, 1894

There isn’t a lot on the Black Death in medieval literature.

In fact, if you were to rely on the contemporary documents (rather than on the mass graves or posthumously written records kept by the Catholic Church), you would be forgiven for thinking that the plague was a minor event with limited geographical effect.

People were either too traumatized to capture their experience in art or writing, or they were simply too busy dying — after all, we estimate that some 25 million Europeans died from it between 1347 and 1351.

Of course, at some point (in a generation or two), Europe was ready to deal with the trauma of the catastrophe. The occasional engraving or painting appears and stories of saints who died or dealt with the disease begin to be told. Suddenly it becomes clear that Medieval man was quite interested in figuring out why he was dying. Lacking a microscope, he turned to ancient Greece and his faith to explain the phenomenon.

Perhaps the most popular theory had to do with miasma, or bad air. No one was quite sure what exactly caused the air to turn poisonous — although decaying matter, bad smells, and the alignment of planets were all blamed — but it was quite obvious that, if you lived secluded in the countryside, you were much less likely to die than if you lived in the city.

Others were persuaded that nothing less than divine punishment could have produced such a mass of death and destruction so quickly.

As middle schoolers, we all spent a week or two studying the bubonic plague before moving on to discussions of knights in shining armor and castles, but that doesn’t quite capture the persistence of the disease. Sure, the epidemic that occurred between 1347 and 1351 was especially bad, but the bubonic plague didn’t just disappear. On occasion, and without warning, it would rear its ugly head.

Which is why, in the 1890s, Hong Kong was dealing with it. This time, however, the world was ready.

Japan had opened itself up to the West for trade some 40 years earlier at the persuasion of Commodore Matthew Perry and was determined not to follow in the path of China and India (both British colonies). It had wholeheartedly set out to modernize its society as rapidly as possible with the hope of being recognized among modern Western nations as a legitimate power.

That meant adopting a new calendar, a new tax system, a new method of social organization, and even a new justice system — all within the span of just a few decades. It meant that Japan, eager to test out its updated military, was rapidly heading toward conflict with China.

Then the plague struck.

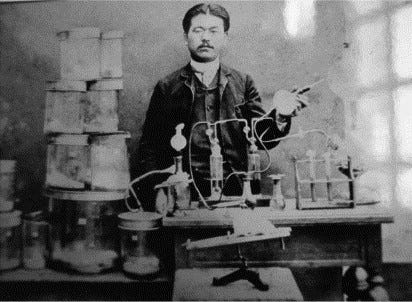

And because this was 1894, Japan and the West sent their best to figure out why. On Aug. 25, 1894, Japanese scientist Shibasaburo Kitasato published a paper in the Lancet, claiming to have discovered the bacteria at fault for the disease while studying patients’ blood in Hong Kong. At almost exactly the same time, Alexandre Yersin (who had also gone to Hong Kong) made the same claim, describing the bacteria slightly differently.

The result was a lot of scientific kerfuffle (eventually, we named the bacterium Yersinia pestis, so it’s fair to say Yersin won) and commotion. This, after all, was the Great Black Death — and now we’d finally figured out its cause. The fix, all this time, turned out to be as simple as antibiotics.